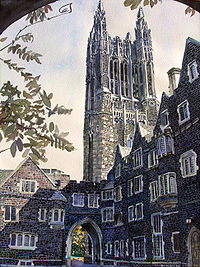

Princeton: The name evokes serious scholarly pursuit. Among its alumni are governors, senators, presidents, Supreme Court justices, admirals, rocket scientists, inventors, Pulitzer and Nobel Prize winners, and a few bona fide Hollywood stars.

Princeton: The name evokes serious scholarly pursuit. Among its alumni are governors, senators, presidents, Supreme Court justices, admirals, rocket scientists, inventors, Pulitzer and Nobel Prize winners, and a few bona fide Hollywood stars.

It stands to reason that a quintessential university town like Princeton would have an independent bookstore. For 26 years, Micawber Books was that store, until the owner decided to close for personal reasons. . Meanwhile, the township built a new library and just outside the town limits, Barnes and Noble had customized a branch to draw the Princeton clientele by including knowledgeable information specialists, a large supply of arcane books and a roster of top-drawing guest speakers. No one was quite sure whether the town would see another independent bookstore.

Enter Labyrinth Books. After making sure Micawber’s owner was truly out of the bookstore business (“We would never have come to a small town and displaced a quality independent store with deep roots in the community,” says Labyrinth owner Dorothea von Moltke), the new store opened in 2006, backed by a partnership with the University and a strong wholesale business. Add to that an ambitious community outreach, and Labyrinth appears to have hit on a winning formula.

The retail establishment is just what you want in an indie book store. Unusual and unexpected books are more likely to grace the windows than are best sellers, although those are also on hand. Nearly every weekend, the bins are placed outside, where they become part of the busy main street culture that attracts many tourists in addition to students and members of the local community. Labyrinth doesn’t have a coffee shop and products like mugs, bookmarks, and calendars are kept to a minimum, especially since they can be found in the University gift shop next door.

The retail establishment is just what you want in an indie book store. Unusual and unexpected books are more likely to grace the windows than are best sellers, although those are also on hand. Nearly every weekend, the bins are placed outside, where they become part of the busy main street culture that attracts many tourists in addition to students and members of the local community. Labyrinth doesn’t have a coffee shop and products like mugs, bookmarks, and calendars are kept to a minimum, especially since they can be found in the University gift shop next door.

Labyrinth and its helpful website are both organized “so you can find what you didn’t know you were looking for.” True, but the wide variety of categories makes it likely you’ll find what you were hoping to find. The business of book–buying, browsing, reading and discussing–is what Labyrinth is all about

Dorothea and her husband met in New York; she was finishing her PhD at Columbia University and he was co-owner of the nearby store, BookForum. In the mid-nineties, the couple founded Great Jones Books, which has become nationally recognized as a wholesaler of quality hurts and remainders.

Labyrinth Books opened a retail store in New Haven, close to Yale University more than a decade ago. The owners established strong ties to the faculty and students. But Yale’s administration chose as its official partner the Barnes and Noble branch just around the corner from Labyrinth. “To say that [Yale] did nothing to support the presence of an independent, scholarly and community bookstore in town is, unfortunately, even a bit of an understatement,” notes von Moltke pointedly. The New Haven store closed in May of 2011.

In Princeton, however, Labyrinth has a true collaboration with the University and remains its official source for all required course books as well as important ancillary materials. The bookstore is next to the University store; both do a brisk trade, especially on weekends. A new pilot program launched in September offers students 30% off. Discounts are also available to faculty. The University sponsors events at the store; Princeton professors are often guest speakers.

The store’s relationship with the community is one of mutual devotion. Labyrinth’d mission–“keeping reading alive and…reaching across intellectual as well as  social divides”—is especially important to the highly educated, culture-loving residents. Program co-sponsors have included the Princeton Public Library (itself a significant cultural presence in the community), the Princeton Research Forum, Trenton Crisis Ministries, Sustainable Princeton, the Lewis Center for the Arts, and Princeton’s well-regarded McCarter Theater, to name a few. Labyrinth has also established, with carbonfund.org, a unique program designed to offset the carbon foot-print of any book purchased from the store for an additional five cents per book, that sum matched by the organization. Von Moltke believes these partnerships enable Labyrinth to “keep questions of social justice as well as the viability of the arts at the forefront of our concerns.”

social divides”—is especially important to the highly educated, culture-loving residents. Program co-sponsors have included the Princeton Public Library (itself a significant cultural presence in the community), the Princeton Research Forum, Trenton Crisis Ministries, Sustainable Princeton, the Lewis Center for the Arts, and Princeton’s well-regarded McCarter Theater, to name a few. Labyrinth has also established, with carbonfund.org, a unique program designed to offset the carbon foot-print of any book purchased from the store for an additional five cents per book, that sum matched by the organization. Von Moltke believes these partnerships enable Labyrinth to “keep questions of social justice as well as the viability of the arts at the forefront of our concerns.”

Princeton is home to a great many writers, some quite well-known and others less so. The store is generous in giving both established and relatively unknown authors time and attention (author’s note: I gave a reading at the store, which carries my book, in 2010).Whereas Barnes and Noble might sniff at a pitch from an author without a national platform or a slot on the best-seller list; Labyrinth will offer a place in its events calendar for a reading/book signing and free publicity through its mailing lists.

Labyrinth’s bread and butter comes from its business as a highly reputable and nationally recognized scholarly book wholesaler. “To be the booksellers we are,” von Moltke says, “we need also to be book-wholesalers; [we are] constantly looking for the best books at the best prices.” GJB buys titles “by the truckload” at auction, keeps what’s best for the store, catalog, and retail website, and sells the rest to bookstores nationally and internationally. GJB has a warehouse not far from Princeton in Pennington, New Jersey that carries more than 50,000+ titles at discounted prices, “more than the largest of chain stores,” according to von Moltke. The idea is to source books that the ever-churning marketplace has given up on; giving them a longer life by bringing those books back into circulation and selling them at deep discounts. The process is designed to allow both GJB and its retail store to compete with chains and online retailers

Businesses like Amazon present a challenge, von Moltke admits. “Here you have a bookseller for whom books are effectively lost leaders for selling other products such as cosmetics, electronics, and all the rest,” she explains, adding, “Competing with a ubiquitous bookseller who is not looking to make any money on books will always be tricky.”

The future of print material is another question mark in terms of the viability of the Labyrinth model. The owners are already looking ahead: they are hoping to acquire a print-on-demand machine (called the espresso machine), which would allow them to print any book in the public domain as well per-copy self-published books and perhaps even current titles, once publishers warm to the idea. Says von Moltke with obvious enthusiasm, “This would mean we would never have to say to a customer that we don’t have a book. Instead, we’d tell them: give me 2 minutes.”

The owners seem to have hit upon a way to survive and thrive: the small store is backed by a successful wholesale book business with a huge list and deep discounts. In the end, it’s all about the culture of reading. Labyrinth is devoted to providing its customers with any book, anytime–the ones they need and the ones they didn’t know they wanted. What more could any of us ask from an independent bookstore?

Labyrinth Books

122 Nassau Street

Princeton, NJ 08540

www.labyrinthbooks.com

top image: en.wikipedia.org

Chris finger-pointing

Chris finger-pointing

I couldn’t hear what was being said; I’ve read elsewhere that a dedicated corps of occupiers is meeting to try and devise a set of demands. Sure there are some goof-offs, but the few protesters I encountered in my all-too-brief sojourn both wanted a change to a skewed system and felt frustrated that they were characterized as slackers or whiners, or insufficiently prepared to take on the entire system by which banks and businesses that don’t create jobs and CEOs who don’t produce dividends are nevertheless rewarded.

I couldn’t hear what was being said; I’ve read elsewhere that a dedicated corps of occupiers is meeting to try and devise a set of demands. Sure there are some goof-offs, but the few protesters I encountered in my all-too-brief sojourn both wanted a change to a skewed system and felt frustrated that they were characterized as slackers or whiners, or insufficiently prepared to take on the entire system by which banks and businesses that don’t create jobs and CEOs who don’t produce dividends are nevertheless rewarded. remember registering on Classmates but who knows? I might have hit the wrong button at some point. The bottom line is: he found me.

remember registering on Classmates but who knows? I might have hit the wrong button at some point. The bottom line is: he found me.

Always on My Mind

November 21, 2011 by 1 Woman

Aren’t we just full of opinions? As a friend of mine wrote in her book: “[While} having so many ways to bring our opinions into public discussion has been, on the whole, a terrific development… not all ideas are equal―equally valid, equally worthy, equally verifiable.” In a related article, she noted: “the opportunity to comment doesn’t mean we’re required to put in our two cents, notwithstanding our collective compulsion to do so.” However, she also recognized that the horse is out of the barn (or maybe the train has left the station; you get the drift) when it comes to opinionating—many of us are likely to grab any and every opportunity to opine–the least we can do is make every attempt to make an expressed opinion as informed as possible.

My name is Nikki Stern and I approve this message. Okay, I wrote this message, in my book Because I Say So and in an article called “IMHO” I bring this up because I’ve found myself this fall throwing opinions all over the place: on my blog, on Facebook, on the website I publish (Does This Make Sense) and, most recently, in the New York Times.

Opining on the Times website isn’t like opining on AOL. By and large, the commenters are smart, well-read and restrained in their responses (of course the Times screens the comments before publishing them, so perhaps I’m just not seeing the “!%$&@)%(*^*” versions that come into the editors’ inboxes. What this means is that if I have an impulse to comment, I know I’d better make sense. In part, it’s my ego at work: I don’t want appear to be a complete idiot. On the other hand, who’s going to remember commenter #49 on the recent Charles Blow or Frank Bruni op-ed? Exactly: no one. Still, I feel a certain responsibility to sound intelligent—to be intelligent.

Of course I’d like to attract a little attention on behalf of whatever I’m promoting (a book, a blog) before my comment scrolls by and disappears into the ethos. This can be achieved by obtaining “recommendations” which are garnered when the reader hits a little button at the end of the comment and which means said comment may be highlighted on the site. Gad, everything’s a competition these days!

The situation causes me to hesitate before I comment (a good thing), and then, if I decide to post my thoughts, I will write out and carefully proof them before I hit “send” (an even better thing). Sometimes, thanks to the unpredictability of the keyboard and the undeniable fact that my brain works faster than my fingers, I may end up with a typo. But my thoughts are nearly always clear.

I also read other comments on the post where I’ve left my comment but also on other pieces I find provocative (or pieces I don’t understand). If Paul Krugman tells me why the Euro is a terrible idea, I want to read what more knowledgeable people have to say on the subject. Granted, Krugman is a Nobel Prize-winning economist and some of the commenters don’t know the difference between a derivative and a derivation but I’m frequently surprised about the level of thought and intelligence that goes into the replies. At the very least, I get more background and more history.

I also read letters to the editor for my favorite magazines. Sometimes I try to read comments and letters in magazines I don’t care for, like Reason Magazine (I don’t really dislike the magazine, but some of the articles in Reason–which purports to be a libertarian magazine–are pompous in the extreme); or letters in magazines I don’t care about. I love reading the letters section in New York Magazine because they aren’t simply letters but blog postings, tweets, passing comments—all reactions to the often provocative stories within. Like Vanity Fair and The Atlantic, the magazine makes a big deal out of noticing and promoting and replying to and arguing with the people who are noticing and replying to and arguing about something they read (which means they’re promoting it, of course).

Everyone has an opinion; no doubt about it. And everyone wants their opinions to count. One way to do that is to use your opinion as a way to start a conversation or encourage a response; to learn something from other opinionators; to practice writing clearly and concisely; to get better at framing an argument; to think, to review your own feelings about a topic, to get in the game. We might not all end up as recommended picks or one step closer to our own op-ed column, but we’ll be smarter commentators. And that means we’ll be smarter citizens.

Posted in Culture, In The News, Life, Media, Politics | Tagged bloviator, commentator, New York Magazine, New York Times, op-ed, opinion, Reason Magazine, talking head, The Atlantic, Vanity Fair | 4 Comments »